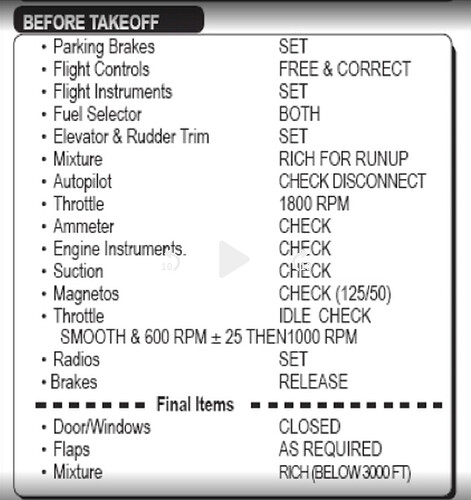

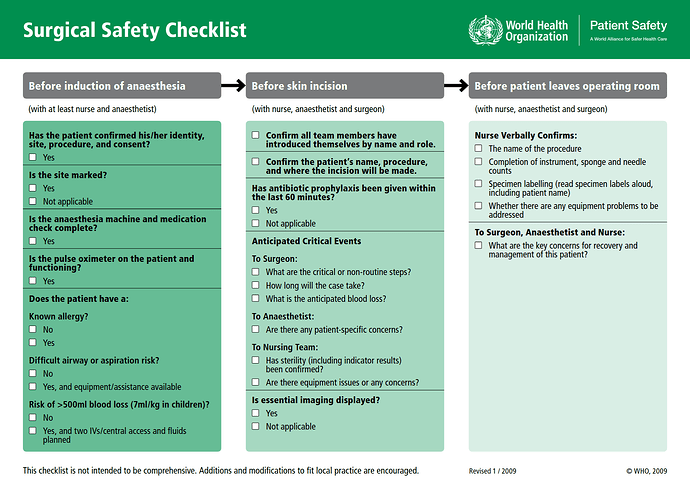

Atul Gawande is a surgeon who was interested in reducing mistakes in surgery. So he looked to other industries like airline pilots and construction of large buildings. What he found was the simple checklist.

The common thing in our modern world is that things are becoming more complex. It is beyond the ability of any one person, even the best, to execute flawlessly every time. Additionally, good collaboration is critical when things go wrong. The checklist is the solution. Not a comprehensive document that covers everything list, but a concise as possible list that addresses the biggest issues and encourages the participants to gel into a team when facing a task.

In the past, autonomy was valued – the self-sufficient doctor who ran everything and had all the answers. Today, the world is too complex for that to work very well. Ironically, it is the simple checklist that helps shift this balance of power to where it is needed – the nurse who notices something the surgeon overlooked, etc.

Checklists help us get the simple things right so we can focus on the hard things.

The interesting thing about this book as it seems applicable to any industry that faces complexity.

A few quotes:

What is needed, however, isn’t just that people working together be nice to each other. It is discipline. Discipline is hard–harder than trustworthiness and skill and perhaps even than selflessness. We are by nature flawed and inconstant creatures. We can’t even keep from snacking between meals. We are not built for discipline. We are built for novelty and excitement, not for careful attention to detail. Discipline is something we have to work at.

You want people to make sure to get the stupid stuff right. Yet you also want to leave room for craft and judgment and the ability to respond to unexpected difficulties that arise along the way.

Good checklists, on the other hand, are precise. They are efficient, to the point, and easy to use even in the most difficult situations. They do not try to spell out everything—a checklist cannot fly a plane. Instead, they provide reminders of only the most critical and important steps—the ones that even the highly skilled professionals using them could miss. Good checklists are, above all, practical.

Here, then, is our situation at the start of the twenty-first century: We have accumulated stupendous know-how. We have put it in the hands of some of the most highly trained, highly skilled, and hardworking people in our society. And, with it, they have indeed accomplished extraordinary things. Nonetheless, that know-how is often unmanageable. Avoidable failures are common and persistent, not to mention demoralizing and frustrating, across many fields—from medicine to finance, business to government. And the reason is increasingly evident: the volume and complexity of what we know has exceeded our individual ability to deliver its benefits correctly, safely, or reliably. Knowledge has both saved us and burdened us.

Anyone who understands systems will know immediately that optimizing parts is not a good route to system excellence

They chose to accept their fallibilities …